The

Hamptons It's Not

By

FIELD MALONEY

Copyright 2001 The New York Times Company

September 2, 2001

Ride the A train out from Manhattan to my summer bungalow in the Rockaways. Crossing Jamaica Bay, I get a little lightheaded. The subway car, which has been chugging along over the bay, plunges downward with a jerk, as if it's headed straight for the bottom. Then abruptly, almost at the waterline, the car seems to skim right across the top of the waves. It's as if a gust of wind could swirl up and tip it over. Hitting open water in a crowded New York City subway car is one of the strangest satisfactions of metropolitan life.

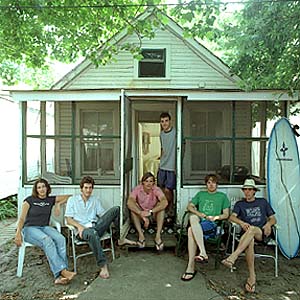

This

summer, with four men and three women, I rented a summer share in Rockaway

Beach, Queens. We work together at a magazine in the city, and don't

make a lot of money. We had found our own beach house for only $250 apiece

for the whole summer, and we felt wildly lucky. All I knew about

the Rockaways was that it was at the far end of a subway line, on

the ocean, and that there was a punk song that went:

This

summer, with four men and three women, I rented a summer share in Rockaway

Beach, Queens. We work together at a magazine in the city, and don't

make a lot of money. We had found our own beach house for only $250 apiece

for the whole summer, and we felt wildly lucky. All I knew about

the Rockaways was that it was at the far end of a subway line, on

the ocean, and that there was a punk song that went:

The

sun is out and I want some

It's

not hard, not far to reach

Rock

rock Rockaway Beach

Rock

rock Rockaway Beach.

At dusk the night before Memorial Day, I packed up my surfboard in its shiny silver case, ducked down into the subway and headed out with two housemates to the Rockaways for the first time. My companions: a tough-nerved editorial assistant and a fact checker who claims to have body-surfed 6,758 waves.

Our

bungalow sat off Beach 101st Street, in an alley where two rows of

cabins were squeezed together like roosting hens. It was two blocks from

the ocean, three blocks from a sewage treatment plant, and not much bigger

than some people's tool sheds. At the turn of the century, this land

was part of a giant open-air colony where for $300 a family could

rent a tent for the summer. The bungalows were built right before

World War I in Gravesend, Brooklyn, to house Army officers, and then

hauled to the Rockaways by barge.

Our

bungalow sat off Beach 101st Street, in an alley where two rows of

cabins were squeezed together like roosting hens. It was two blocks from

the ocean, three blocks from a sewage treatment plant, and not much bigger

than some people's tool sheds. At the turn of the century, this land

was part of a giant open-air colony where for $300 a family could

rent a tent for the summer. The bungalows were built right before

World War I in Gravesend, Brooklyn, to house Army officers, and then

hauled to the Rockaways by barge.

Since the 1940's, more than 100 of the bungalows were used as private residences in a community called the Marcellus Colony. In 1985, 17 of them united as the Seashell Gardens Association. Ours was chipped, tattered, flaked and windbeaten, but otherwise much the same as when it was built.

In

the front was a narrow, screened-in porch carpeted with AstroTurf.

Inside was a daybed covered by a madras bedspread, a kitchen table

with a brown plastic tablecloth, and, in back, two bedrooms, separated

from each other by paper-thin, head-high wood partitions. Strings

dangled from bare light bulbs that had been fastened to the pine

rafters. Synthetic Irish

lace

curtains hung primly in the windows.

The bathroom was the size of a phone booth. On the wall was a sign. In faded 50's typescript, it listed the rules of the house and concluded: "Remember This Is Your Home for the Summer. Be Proud of It."

The

bungalow, which had been meant for a small family, felt crowded with just

the three of us. A plane taking off from Kennedy Airport roared past,

so low that the house shook. A lanky 13-year-old strolled by the

porch like a pasha, a brown python draped around his neck, a twittering

pack of younger boys in his wake. Soon we heard barks and shrieks.

The boys had

decided

it would be fun for the snake to meet the neighborhood pit bull.

We sank into mattresses that sagged on broken springs; our beds felt

as if they might swallow us whole.

"It's pretty small," the fact checker said. "Yes," came the reply from across the partition. "Small."

The

Rockaways are a sandy strip of barrier beach at the southern shore

of Brooklyn and Queens. In the 19th century, Rockaway boomed as a

summer resort, with many hotels, both the fancy and the flophouse variety,

along with bathhouses, saloons, amusement parks and brothels. New Yorkers

came in droves until World War II, after which Rockaway began a long, slow

decline from which it still hasn't emerged.

The

Rockaways are a sandy strip of barrier beach at the southern shore

of Brooklyn and Queens. In the 19th century, Rockaway boomed as a

summer resort, with many hotels, both the fancy and the flophouse variety,

along with bathhouses, saloons, amusement parks and brothels. New Yorkers

came in droves until World War II, after which Rockaway began a long, slow

decline from which it still hasn't emerged.

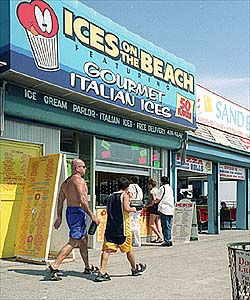

The number of summer renters shrunk drastically. These days most Rockawayans, even the bungalow dwellers, live there year round. The famed Boardwalk that stretches along six miles of shoreline and has the middling honor of being the world's second- longest, behind Atlantic City, now runs past drab high-rise apartment complexes, housing projects, acres of overgrown vacant lots and faded pastel buildings: hourly hotels, halfway houses and nursing homes (80 percent of Queens nursing homes are in Rockaway).

There are still some shiny, affluent neighborhoods on Rockaway's West End, but much of the peninsula has a wistful, bleached-out quality - gritty and definitely urban - that has the desolate beauty of an early Bruce Springsteen song.

When I mention my "summer share in the Rockaways" to Manhattanites, I get several types of responses: the scrutinizing, eyebrow-raised glance that means, "You're joking, right?"; blank incomprehension: "Where? There's an ocean there?"; and the knowing reminiscence that usually begins with something like, "Back in high school" and continues to, "Ah, Rosalita in the two- piece at the disco beach with that snake tattoo you know where" and takes another 20 minutes to finish. A man who'd spent his youth in Rockaway said, "You'd better not turn it into another Williamsburg."

When

I mentioned my bungalow at an Upper East Side dinner party, the hostess

instructed me not to refer to my summer plans too loudly in good

company. I did not tell her the cream of New York society used to go out

to Rockaway. In the mid-19th century, Vanderbilts, Astors, even Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow stayed at the Marine Pavilion, Rockaway's first grand

oceanfront

hotel.

Back then, elaborately dressed women clambered into beachside cabins to change; at a signal, pack horses towed the cabins out into the water so the women could discreetly float out into the surf. After the Civil War, large numbers of Irish immigrants came out to escape hot tenements, and when some of them got rich, they took over the old WASP summer strongholds. Far Rockaway became known as the Irish Riviera.

I

began going to Rockaway alone, on some weeknights when the house

was empty. I had grown up on a farm in rural Massachusetts where

the rhythm of summer days was marked by alternations of physical

work and breaks to swim in the cold river down the road, and in Rockaway,

I returned to that. I'd drop my bag at the cabin, put on my trunks and

go to the water, waving to the boys in the alley. (They'd found a new pastime,

climbing onto the roof of a shed at a nearby sweater factory and hurling

themselves into thick piles of garbage bags filled with yarn.)

I

began going to Rockaway alone, on some weeknights when the house

was empty. I had grown up on a farm in rural Massachusetts where

the rhythm of summer days was marked by alternations of physical

work and breaks to swim in the cold river down the road, and in Rockaway,

I returned to that. I'd drop my bag at the cabin, put on my trunks and

go to the water, waving to the boys in the alley. (They'd found a new pastime,

climbing onto the roof of a shed at a nearby sweater factory and hurling

themselves into thick piles of garbage bags filled with yarn.)

Usually

it was dark or nearly dark when I swam, and the onrushing surf would

lapse in and out of focus. I couldn't see the lines of waves so well,

and all of a sudden I'd be surprised by a big one right in front

of me. I'd float in the surf on my back, looking toward the shore.

The street

lights

that lined the Boardwalk ribboned across the shoreline like the dotted

yellow lines on a highway. Afterward I'd sit, sopping wet, in the

empty lifeguard chair and eat my dinner.

The bungalow had no phone, so on the way home I sometimes stopped at the phone booth on the corner to call my girlfriend, who had begun to accuse me of loving Rockaway more than I loved her. The phone booth was near the New Irish Circle, a popular Irish bar, and as I held the receiver, still sopping wet in my flip-flops and a towel, streams of girls dressed for a night out would pass by, leaving a summer trail of hair spray, laughterand perfume.

We

decided to have a big Fourth of July party in Rockaway. It rained. We sat

on a concrete wall in the Beach Channel High School parking lot and

looked across Jamaica Bay toward Manhattan, waiting for the Macy's

fireworks. All we could see was fog and darkness and the outline

of the

Marine

Parkway Bridge. There were one or two small flashes of light across

the bay.

"There they are!" someone said.

"No, that's Brooklyn," a middle-aged couple corrected him.

Finally, we watched a guy wave a sparkler around for awhile. Don Henley's "Boys of Summer" blared from an open Trans-Am parked behind us. A police car came and told us all to leave.

We didn't end up having to do the car- with-30-clowns trick very often; rarely did more than four people sleep in the bungalow at once. One housemate, a rocker girl who commuted to work from her parents' house in New Jersey, made it out to the bungalow only twice. Another housemate, a Lower East Sider with a domesticizing touch, on her first visit neatly set out a pair of tiny rainbow flip-flops; hung up in the closet an 80's concert T-shirt and a pair of plaid flannel pj's; and put on the shelf in the bathroom a small bottle of shampoo and a toothbrush. She never came back, and everything is still where she put it.

But a bunch of us came out at least once every weekend. The fact checker became enamored of the pretty girls at the New Irish Circle and was always searching for excuses to head out there, especially on Thursday nights: D.J. Hip Hop Healy's Top 40 dance party.

Another housemate, a born and bred Manhattanite, was reunited on the Rockaway Boardwalk with a long-lost childhood love, Whaleamena, the giant gray and aquamarine stucco whale that he used to clamber over as a boy in the Central Park Zoo and that has beached on Beach 95th Street and is now in better shape than it was back then. (Animal activists note that the Central Park seal statue is also alive and well, up the Boardwalk from Whaleamena.)

The Rockaways, which might complain about being a dumping ground for public housing, bad Robert Moses projects and methadone clinics, also seem to be a dumping ground for silly Manhattan sculptuary. Even a painted cow from last summer's Cow Parade stands on Beach 110th Street, its head half severed from its neck.

You would think that with young tenants, hot summer nights and moonlit waves, our bungalow would have been a hotbed of romance. But the walls were so thin that any coupling would have been public coupling.

At

first glance, Rockaway Beach seems to be like any other public beach,

just one long strip of sand with people on it. But the natural segregations

of city life seem to follow New Yorkers when they get off the A train

or the No. 53 bus from Queens.

At

first glance, Rockaway Beach seems to be like any other public beach,

just one long strip of sand with people on it. But the natural segregations

of city life seem to follow New Yorkers when they get off the A train

or the No. 53 bus from Queens.

On the beach, I asked a few of Rockaway's Sunday sociologists to explain. Public beaches here are tribal, they said. In the 1980's, Beach 116th and 117th was the heavy metal beach. (Tattooed guys, bikers, Ozzy Osborne T-shirts.) Now it's the Brazilian section. (Are those things really bikinis?) Beach 108th, the Italian section, was called Disco Beach because of the "Italian boogie freaks."

Beach 98th Street belongs mostly to Puerto Ricans, who hold all-day picnics in the slatted shade under the Boardwalk. Ninetieth is the surfer territory. Surfers cluster out in the waves, their bare heads and black wet suits poking out of the water, making them look like packs of seals. Further down are the Russians.

It's all pretty simple, a Rockaway man with a silvered walrus mustache told me: "If you see little kids in underpants, it's a Puerto Rican beach, if you see grown men in their underpants, it's the Russian beach."

If

the Rockaway Beach is a series of ethnic fiefs, the lifeguards are

still the lords. They sit on their wooden towers and survey their domains

in bright orange body suits (or if it's really hot, just a bathing

suit). One day, I saw a woman carried out to sea by a riptide.

The beach was

packed

and had that lazily anarchic quality found when hundreds of barely

clothed men, women and children are all trying to be leisurely at

once.

Everything froze as four guards dashed across the sand carrying life preservers. A heavyset woman with long black hair was far out in the break, waving her hands. It was amazing to see the jaded lassitude that the lifeguards maintain so well on their towers snap so suddenly into pure focus. One after another, they dove into the surf and took hard knife strokes through the waves. In a second, they had formed a ring around the woman and hauled her to shore.

"I just grabbed her," a lifeguard with freckles and a crew cut told me. (The lassitude had quickly returned.) "The bad thing is when you go in and break your shades. Put that in the paper."

Further

down the beach that day, I saw a man in a blue zebra-print Speedo

chase after a large seagull. He tackled the squawking bird, wrested

it to the ground and pried open its beak. Out popped a yellow parakeet.

The man, whose name was Robert, was from Howard Beach, and the bird was

his pet, Peggy Sue. He has two others.

Further

down the beach that day, I saw a man in a blue zebra-print Speedo

chase after a large seagull. He tackled the squawking bird, wrested

it to the ground and pried open its beak. Out popped a yellow parakeet.

The man, whose name was Robert, was from Howard Beach, and the bird was

his pet, Peggy Sue. He has two others.

"Hey, they get warmed up like you and me," he said. "That's why we go to the beach. They like to go frolic in the water. I teach them to swim in the bathtub."

I woke up one morning in Manhattan to find the Rockaways plastered across the front page of all the newspapers. Three teenage girls had drowned in the surf off Far Rockaway, a few miles down the shore from our bungalow. An hour before the lifeguards came on duty, they had been sucked out to sea by a nasty riptide.

The night after the drowning, I got out of work late and went out to the Rockaways with two housemates. It was one of those desperately humid August nights that ushered in the heat wave - and we went swimming. The moon was almost full, and it lit up the beach like a giant street lamp.

There were no lifeguards, of course, and swimming was prohibited. I had expected the beach to be empty. But two men swam right next to us and then sat on the sand staring out at the ocean. People were having picnics, salsa blared out of boomboxes. I passed by the dark silhouette of a couple making love in a lifeguard tower. I never again saw the beach so busy at night. At 2 o'clock, it still hadn't emptied out.

A few weekends ago we had a big party. Streams of people moved between the beach, the porch and the kitchen table. We played football on the sand at midnight. We swam, even though it was the weekend of squid eggs - translucent, gelatinous things that littered the surf - and it was like swimming in wet tapioca pudding.

That night we slept seven: two to each single bed, one in the daybed and one on the floor. I put a sheet on my silver surfboard cover, set it on the porch AstroTurf and slept very well.

And

another thing. We're not leaving on Labor Day. We've extended our

lease for another month and will stay in our bungalow through September.

Maybe even longer. October and November are hurricane season, and the waves

get really big.

Copyright

2001 The New York Times Company